Applications for Small Wind Turbines

Small-scale wind energy is a small but rapidly growing segment of the RE industry in the US. Like other renewable sources, in its initial stage, the cost of small wind electricity is generally less competitive when compared to current market prices of traditional energy sources. Thus, in an effort to support RE development, many US states have adopted a variety of policies to encourage small wind power. This is in line with the oft-cited idea of states serving as “laboratories of democracy” to experiment with a variety of policy tools.

Since the 1990s, technological development and the expansion of wind technology use have been markedly prominent among the renewable technology of electric generation. The wind energy industry was established commercially through large incentives arising from the adoption of normative and institutional instruments through the support of the National States or regional economic blocks. Such incentives provided the construction of a solid industry that evolved both in the conception and in the process of building and operating its projects. However, this market is sharply structured into large projects, based on the concept of "wind farms" interconnected to the network, a process that relegated small projects to a low profile and limited incentive plans.

Until the 1980s, the focus was on small-scale technologies, and the capacity of most commercial models was below 100 kilowatts (kW). Most turbines have been installed in rural or isolated areas since the initial stages of its development at the beginning of the 20th century, but they are also deployed in developing countries. Electric power supply and water pumping are still the main applications of the technology, both in urban households and rural areas worldwide. Possible applications for SWTs are: electric power generation for households; electric power generation for industries and commerce; electric power generation for farms and isolated villages; use in boats; use in hybrid systems for electric power generation; water pumping; use in desalinization and purification systems; remote monitoring; educational systems; researches and telecommunication systems.

In spite of the current consolidation of the large wind market, small wind power is still in its initial stages. The situation is different in China and the United States, where the installed capacity in 2018 was 573.57 MW and 150 MW, respectively. It should be pointed that between the years 2013–2018 the rate of growth was over 50%, as shown in Table 1:

| Country |

Installed Capacity (MW) |

||||||||

|

Cumulative Years before 2012 |

by Year |

Cumulative Years before 2018 |

|||||||

| 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | ||||

| Brazil |

0.00 |

0.03 | 0.02 | 0.11 | 0.04 | 0.11 | 0.09 | 0.40 | |

| China |

280.01 |

72.25 | 69.68 | 48.60 | 45.00 | 27.27 | 30.76 | 573.57 | |

| Germany | 24.55 |

0.02 |

0.24 |

0.44 |

2.25 |

2.25 |

1.00 |

30.75 |

|

| South Korea | 2.99 | 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.09 | 0.79 | 0.08 | 0.06 | 4.08 | |

| United Kingdom | 77.98 | 14.71 | 28.53 | 11.64 | 7.73 | 0.39 | 0.42 | 141.40 | |

| United States | 130.73 | 5.60 | 3.70 | 4.30 | 2.43 | 1.74 | 1.50 | 150.00 | |

| Other countries | 626.80 | 8.64 | 17.59 | 16.04 | 63.30 | 80.85 | 13.28 | 826.51 | |

| Global | 1143.06 | 101.27 | 119.82 | 81.22 | 121.54 | 112.69 | 47.11 | 1726.71 | |

| Global (cumulative) | 1143.06 | 1244.33 | 1364.15 | 1445.37 | 1566.91 | 1679.60 | 1726.71 | 1726.71 | |

International literature displays a consensus about the definitions of microgeneration and minigeneration. According to the American Wind Energy Association (AWEA), SWTs are defined as having a generating capacity of up to 100 kW (60 ft rotor diameter). In Brazil, according to Resolution 438/2012 of the Brazilian Electricity Regulatory Agency (ANEEL), small wind systems are categorized as power stations (which could be composed of one or many wind turbines) with a total rated capacity below 100 kW. In general, wind turbines integrated into buildings, as well as any other technology of distributed power generation, have the same goal of decreasing monthly costs of electric power, providing part of the electricity demand consumed at the location.

Developing countries are a great opportunity for the expansion of the small wind market, especially in regions where the wind potential is notoriously favorable to power generation, allowing for its expansion to be based on low-carbon technologies. Nowadays, commercial models of large wind turbines use the horizontal axis orientation, making SWTs more versatile since they are commercialized with either a horizontal or vertical axis, with the horizontal design being significantly more common according to the World Wind Energy Association (WWEA). Despite the considerable amount of models above 10 kW, most commercial models available are below 5 kW. Only 25 manufacturers worldwide have the capability to fabricate turbines between 50 kW and 100 kW.

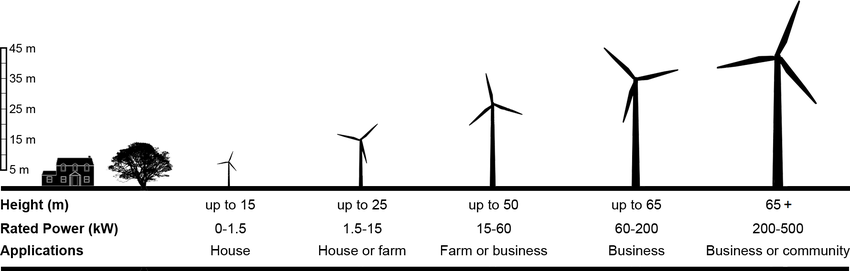

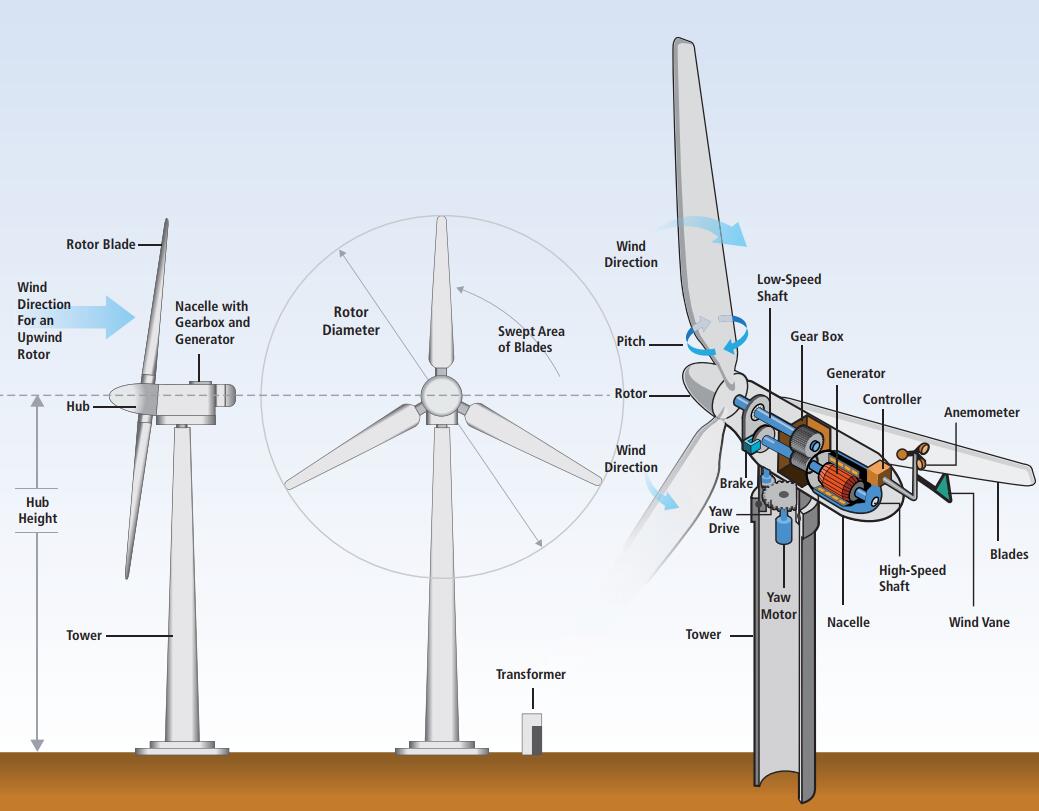

Wind turbines have many sizes and applications, varying from a small turbine deployed to feed a dedicated battery to a set of wind turbines for a department store or factory, and this diversity is considered one of their strengths. For their installation, consumers consider cost, reliability and performance. These variables are a function of wind speed and profile, its intensity and direction and topography, which define the amount of energy provided by the wind turbine. Furthermore, one must consider whether or not there is an electrical distribution infrastructure in the surrounding area. The figure illustrates in a simplified manner the typical applications of SWTs and their dimensions, indicating that the annual energy generated is a function of the installed capacity, which increases as the tower height and rotor diameter increase. The surrounding environment also influence system performance.

Benefits and Challenges

Small wind power is very close to the daily lives of people since the technology does not require large areas or transmission lines. Moreover, they are appropriate for smart grids in the context of distributed power generation. When compared to other technologies of the same power level, wind turbine maintenance is simple. While the output improves when SWTs are combined with other sources to compose a hybrid system, the cost per kW is still higher than that for large-scale plants.

The technological development of SWTs has been significant, which is proven by the many types, sizes and control techniques of the products, but few are available for building integration. Once again, the two main wind technologies are Horizontal Axis Wind Turbines (HAWT) and Vertical Axis Wind Turbines (VAWT). HAWTs are better known, have good performance and are cost effective, favoring their integration. VAWTs, on the other hand, are less efficient in converting the kinetic energy of the wind into electric power. However, they are more resistant, their integration is much better accepted by architects and users, they are safer due to less vibration, and lastly, they take more advantage of the turbulent wind of building rooftops.

It is necessary to consider issues related to the structure of the building during the installation of a turbine. The rotation of the blades and the dynamic pressure of the wind that reaches the turbine may cause vibrations that will be transmitted to the structure of the building, compromising its integrity. Moreover, their noise must also be taken into account. While the recommendation for large turbines is to not exceed 50 decibels (dB) at night from a 500 m distance, for small turbines installed in urban areas the noise limits should not exceed 43 dB at night and 47 dB during the day.

In fact, there is a scarcity of experimental data regarding installed wind turbines, in particular in urban areas. According to Dilimulati, Stathopoulos and Paraschivoiu, urban settings make it harder to compare turbine efficiencies and the viability of different wind turbines available today. Conventional wind turbines directly located in an urban built environment do not perform well. Some wind turbines, especially VAWTs, still show good results but should be further optimized for urban applications.

Another question regards the sensitivity to sitting, according to DOE, considering the capacity factors for the 44 projects using 10 kW wind turbines in this selected group of projects ranges from 7% to 46%, supporting the idea that siting issues strongly influence capacity factors.

SWTs must meet either the American Wind Energy Association (AWEA) SWT Performance and Safety Standard 9.1-200915 or the International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) 61400-1, 61400-12 and 61400-11 standards to be eligible to receive the Business Energy Investment Tax Credit (ITC) (IRS 2015). Certifying a turbine model to a standard is the industry approach to proving that the turbine model meets the required performance and quality standards.

Certification is also consistent with industry and DOE goals to promote the use of proven technology; raise its competitiveness; and increase consumer, government agency and financial institution confidence and interest in distributed wind. Regarding grid connection, it should be highlighted that the Public Utility Regulatory Policies Act (PURPA) of 1978 requires utilities to connect with and purchase power from small wind energy systems.

Small wind technology is still at its early state and there is a lot of space to improve; promising directions have already been identified. There are still a lot of questions about the performance of wind turbines and their economics, but continuous research in this area will provide some of the much-needed answers.

Post a Comment:

You may also like:

Wind is used to produce electricity by converting the kinetic energy of air in motion into electricity. In modern wind ...

Wind is used to produce electricity by converting the kinetic energy of air in motion into electricity. In modern wind ... With the development of science and technology, energy storage is one of the most effective ways to solve the problem of ...

With the development of science and technology, energy storage is one of the most effective ways to solve the problem of ... Operation in severe climates imposes special design considerations on wind turbines. Severe climates may include those with ...

Operation in severe climates imposes special design considerations on wind turbines. Severe climates may include those with ... Modern, commercial grid-connected wind turbines have evolved from small, simple machines to large,highly ...

Modern, commercial grid-connected wind turbines have evolved from small, simple machines to large,highly ... Small-scale wind energy is a small but rapidly growing segment of the RE industry in the US. Like other renewable sources, in its ...

Small-scale wind energy is a small but rapidly growing segment of the RE industry in the US. Like other renewable sources, in its ...